Based upon the former "Wolf Walk" at the Adirondack Wildlife Refuge

Above, Adirondack Bull Moose, West Branch of Ausable River, in Wilmington Notch,

near Whiteface Mountain, 9/22/12, by Brenda Dadds Woodward

Bull Moose in Highlands National Park, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Sept 2016, by Steve Hall

Bull Moose in Highlands National Park, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Courting Cow Moose, Sept 2016, by Steve Hall

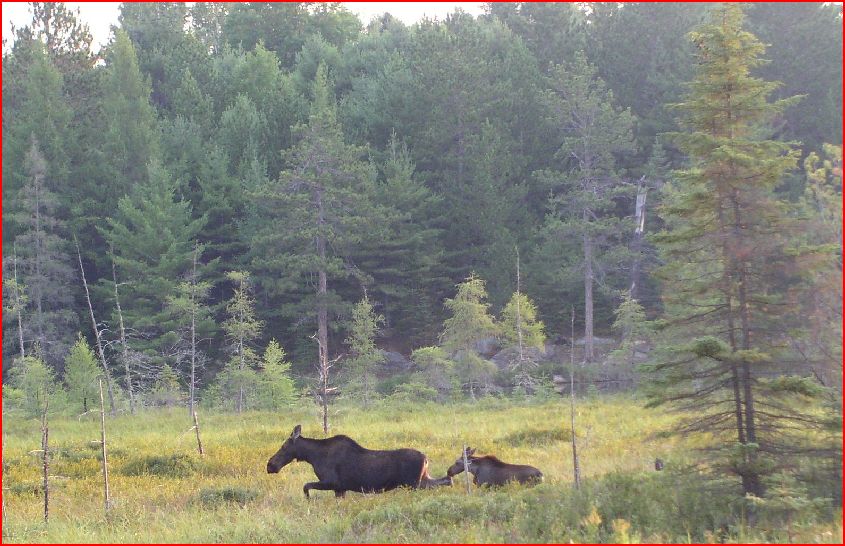

Young Bull Moose in Algonquin Park, June '98, & bull moose in Denali Nat'l Park in Alaska, May 2012, by Steve Hall

Left, Cow with calves in Homer, and right, cow with calves in Kenai, Alaska, May 2012, by Steve Hall

|

"Every creature is better alive than

dead,

men and moose and pine trees, and he who understands this, and he who understands it aright, will rather preserve its life than destroy it." Henry David Thoreau |

Alces alces Order: Ardiodactyla Family: Cervidae Genus: Alces Moose are tragicomic characters in

Nature’s dance of life. While

wolves and bears tend to run

from humans, Moose are more likely to stand there, looking at you with

that

flat, seemingly indifferent stare, if they acknowledge your presence at

all, apparently

fearless, the thumbnail next to the entry "confidence" in the on-line

dictionary. I believe there’s more

at work here

than meets the eye. In their own strange way, moose are cool, and their

numbers

in the Adirondacks, about 800 today, are on the rise, at about a 20%

annual

rate, though climate change may reverse that trend. Moose, the largest member of the deer

family, crossed the Bering Strait land bridge into North

America about 10 to 15,000 years ago, a barely noticeable blink in the

timeline of

life on Earth, and at about the same time our CroMagnon ancestors came

across with their wolf-dog hunting companions. Evolution itself is a

blind architect, fated to perform

modification only, never having that creator’s advantage of starting

from

scratch, with a blueprint unaffected by an existing structure. Moose

speak to

the imperfections of a process in which animals evolve in one

ecosystem,

and then expand into adjoining ecosystems presenting challenges for

which they did not

evolve,

and are not prepared. Moose are enormous, herbivorous

ungulates, with large males

and females weighing in at about 1,500 and 800 lbs. respectively.

Alaskan moose are larger than new England and Eastern Canadian moose,

which are in turn larger than moose found in the western U.S. There’s

much

to recommend the vegan diet, but one shortcoming is the relative lack

of

nutrition. As a result, adult moose have to consume five tons of

vegetation per

year, ranging from cedar and balsam fir branches, and the stems of

deciduous

trees and shrubs in winter, to the leaves and stems of willow, aspen

and birch, as well as aquatic plants in

summer.

This means that moose spend about eight hours a day chewing on fresh

vegetation, and another 8 hours ruminating, rechewing food brought

up from

the fore stomach, or rumen, one of four different chambers in the

moose's

stomach. Aquatic plants fill the sodium deficiency in moose

diets,

which is why we sometimes see them road side, licking the rock salt we

use to

melt winter ice. This also means that the fates of moose

and browse targets such

as cedar and balsam fir are inexorably intertwined, such that a growing

moose population

may cause its own correction by over- browsing balsam fir, causing a

collapse

in the abundance of fir, followed by a collapse in the now starving

moose

population, whose increasing mortality rate makes the wolf’s efforts at

survival much easier and less dangerous, as they can avoid the dangers

of the hunt by scavenging dead moose, leading to an uptick in the

pack’s

numbers, and so on, as the circle of life rumbles on. Bergmann’s rule describes how

individuals within a species

are somewhat larger in colder, more northerly latitudes than in

milder

latitudes, because natural selection works on the tendency for animals

with a

larger body mass to body surface area ratio, to be more effective at

retaining heat,

and therefore more likely to mature, breed and pass along that genetic

advantage to

their offspring. As a result of tens of thousands of years of this

tendency,

moose and

wolves in Alaska are somewhat larger than their counterparts in

Montana, Minnesota and Maine. Mammal hides generally, and moose hides

in particular, are

so efficient at retaining heat, that a visitor to the Refuge, while

watching our wolves running around in playful abandon, and

wondering

what possessed him to visit the Refuge during sub-zero temperatures, quipped that the wolves didn’t seem to know how cold

it was. Even after shedding their winter coats, moose consider fifty

degrees

the optimal temperature. Being in the lake or bog gives them relief

from the

heat and biting insects, and because they can stand comfortably at

depths where

wolves would be quite literally dog paddling, relatively safe from

attack. Moose are solitary

creatures, and don’t generally herd

up the way other ungulates do. Bulls tend to live alone,

and in an

almost comical rebuke to

Intelligent Design, spend 25% of their annual energy input growing

those absurdly

massive antlers, starting in the Spring, using them during the brief

rut season

in Autumn, not only to contest mating rights with other bulls, but as

display

evidence for cows, sort of the moose equivalent of showing off a flashy

car

or

mansion, a clear indication of their strength and suitability as mates.

Many

bulls become so exhausted by the rut, they become vulnerable to wolves,

who

quickly recognize weakness, injury and vulnerability. Moose courtship is

deserving of a romantic comedy. A hairy thin layer of "velvet" covers

the antlers while they're growing, and when the antlers reach full

size, which varies with age, the bulls rake their antlers through

branches and roughage, scraping the velvet skin off the antlers, which

causes the antlers to darken in color.

By mid August,

mature bulls will begin to playfully spar with younger bulls, as a

warmup for the Autumn rut. Generally speaking, neither young or mature

bulls are injured during these sessions, which is not the case when

mature bulls spar with each other. Some bulls are killed, or so

severely weakened, they become easier prey for wolves and bears.

Courtship, whose

purpose is for mature bulls to gather and defend a harem, begins when

the bull gouges a trough out of the ground cover with their front

hooves, and then proceeds to pee in the trough, and the pee could

probably fill a gallon jug. The bull then stomps one of its front feet

into the trough, to splash the pee over their bodies, sort of a moose

cologne. During courtship, the bull may also pee on their own legs to

further accentuate the odor. An analogy would be when you see one of

those commercials where a woman sprays perfume into the air and then

steps into the resulting cloud.

It gets better.

Moose have a nose as sensitive as a bear or wolf, and when moose cows

smell the urine, they'll approach and fight each other over which of

them can roll in the urine trough. Bulls may engage in battle with

other bulls, during the period when they're mating with members of

their harem, but usually relative size sorts out which bull will

dominate. I saw the attached Nova Scotia bull, who was ultimately

scorned by the cow he was targeting, run at and drive off a smaller

bull without any fighting.

Cows are naturally very protective of

their calves, and will drive away predators and other moose, the latter

in response to protecting food sources.

Ask any wolf who’s had his skull caved in by Mama Moose’s sharp and

heavy

hooves, when they got too aggressive with her calf. Like all ungulate

calves, moose need protection as

they’re

only about 30 lbs. when born in May, bulking up to about 300 lbs.

within six

months to be prepared for the hardships of winter. Ungulates tend to struggle more through

a winter of deep

snows, as their relatively heavy torsos and sharp hooves force them to

pole

through snow, while wolves not only have snowshoe-like paws, which

enable them

to distribute their weight effectively, allowing them to run on top of

compacted snow, but share the burden of breaking through lighter,

deeper snow by

following in each other’s wakes, and taking turns leading the pack. White tail deer have been in North

America for 4 million

years, and carry meningeal or "brain worm", giant liver fluke and the

winter tick, parasites

which deer

are able to manage and live with. Moose sharing habitat with deer, pick

up

these parasites, and being relative newcomers to our neck of the woods,

fare

less well. Brainworm and liver flukes

are passed to moose through a cycle involving deer droppings, snail

infection and

the ingestion of leaves contaminated by deer pellets or snails.

Brainworm, which produce larvae on the surface of the white tail brain,

work

through the moose brain tissue, destroying the brain, and causing

weakness,

reduction of equilibrium, disorientation and often death in moose.

Flukes are

rarely fatal, but can work with other health issues to weaken moose and

make

them more vulnerable to wolves and other natural fates. A white tail deer will pass through

winter with up to 300

ticks, and have the ability to detect and remove most of the newly

hatched seed ticks

through

licking and rubbing when the ticks climb aboard in autumn, often in

clumps,

from

vegetation brushed by the deer. The ticks are aided in

this boarding

strategy by their ability to detect the carbon dioxide exhalation of

approaching

mammals, and the fact that excited ticks can quiver, cluster, shake and

flip onto the unfortunate moose, sort of like dog fleas at their own

disco. For some reason, moose either do not feel the ticks, until they

have

climbed

up the torso and the female ticks begin biting and drawing blood, or

they are less able to detect their presence. Ed Reed, a biologist with

the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, pointed out

during a presentation on moose, that moose are not as effective at

grooming as are white tailed deer, and their massive head and stubby

neck

make it difficult to stretch around and reach their hind quarters with

their tongues. In addition, Ed pointed out that the Winter tick passes

through three developmental stages while on the moose, each of which

involves taking blood from the moose. By January, an adult moose may be

carrying

anywhere from 10,000

to 80,000 ticks, and while an individual tick takes an insignificant

amount of

blood, moose can reach a tipping point where the ticks are removing a

significant amount of the blood generated naturally by bone marrow and

haematopoietic cells,

leading to loss of energy. In addition, the itching caused by ticks and

mites

lead the moose to bite at their itchy coats, and vigorously rub their

bodies incessantly

against rough-barked trees, leading to coat loss and possibly

hypothermia. These

factors, when

combined with the lower nutrition intake of moose in winter, which,

following

Bergmann’s rule, exposes the moose to possible starvation, threaten the

moose’s

life, making the stretch between mid-March and mid-May the most

vulnerable period

in an adult moose’s year. Moose tend to be safe from wolf attack

between the ages of

sexual maturity, at about three or four, until they are eleven or

twelve. The

reason is that an adult moose is such a powerful and dangerous

adversary, that naturally

cautious wolves approach about 20 moose for each one they decide to

attack.

Bulls live about twelve to twenty years, while cows may last a few

years longer. Moose spend so much time eating that

they’re not great

wanderers, and may not move more than about forty miles from the area

of their

birth, a distance your average wolf pack may travel in a single day,

during the

course of exploring their territories for moose and other prey. Because

wolves

tend to defend huge territories, averaging about 200 to 400 square

miles, an

individual moose could spend its entire life within a given pack’s

territory. Wolves

concentrate their territory defense by spending more time patrolling

their

territory’s periphery, and may pass through any point on that periphery

every two weeks or so. Just as our visual acuity, and more

precisely our ability to

resolve color, is probably our most important sense when it comes to

memory, it’s

not too much to claim that while sharp eyesight and keen hearing are

indispensable

to wolves, to a large extent the world comes to wolves and other canids

principally through their noses. After bears, wolves have the most

efficient and

sensitive noses in the mammal kingdom, and use that powerful

information

gathering tool, to read the olfactory record of the comings and goings

of prey

and poaching competitors like bears, coyotes, bobcats and other

wolves. Talk about "unnatural selection", all dogs were forcibly bred

out of wolves, the first "hunting

dogs", between fifteen and thirty thousand years ago, according to

archaeology, or about 130,00 years ago, according to DNA studies, which

helps

explain why your dog behaves so territorially, constantly sniffing and

scent marking. Wolves may build

olfactory

memories

of individual prey animals, and may approach the same moose many times

over the

course of its life, probing and testing to see if the moose has become

more or

less vulnerable than it was before. But, alas, moose have much bigger

problems

in nature than living

among wolves. Half of all moose develop arthritis by age ten, due to a

combination of genetic predisposition and maternal malnutrition during

pregnancy, and the fact that moose spend so much time standing and

eating,

supporting those large torsos on their legs. Cartilage in the knee and

hip

joints breaks down, leaving the moose in pain, hobbled by swollen

joints, and,

again, vulnerable to attack by the ever testing and investigating

wolves. Jaw necrosis is another common fate for

moose. Moose haven’t

learned how to floss yet, so the constant overuse of the jaw, and the

fact that

moose are often reduced to chewing on leafless, deciduous stems and

shoots in

winter,

results in the jamming of woody material between the teeth. The moose

will

use its

rough tongue in attempts to dislodge the material, but if it begins to

break

down and rot, the jaw may become infected and weakened, leading to jaw

fracture

during mastication, dooming the moose to slow starvation. Starvation is the number one killer of all

wildlife, moose included, and sometimes the intervention by wolves may

interrupt

a slow and horrible process. Like other large North American mammals,

moose are subjected to enormous pressure from vehicular accidents, as

well as by hunting, whether subsistence or trophy, and their wide and

successful dispersal over much of North America today, is due largely

to the wildlife management processes enforced by state and provincial

governments, and to the North American conservation ethic generally. In short, moose in North America are still strangers in a strange land, and have to overcome significant hardships to survive. No wonder they always look like they have a chip on their shoulders. Steve

Hall

|

Newborn moose calf, Homer, Alaska, May 2012, by Steve Hall

Above, Cow Moose in Algonquin Park '98, & below, with calf, by Steve

Great link for more information on moose and wolves:

http://www.isleroyalewolf.org/wolfhome/home.html

Above, Cow Moose outside east Gate of Yellowstone, near Waipiti, Wyoming, Sept. 2012, by Steve

Above, Cow Moose in Rockefeller Preserve, Grand Tetons Nat'l Park, Sept. 2012, by Steve & Bharath

Above, Cow Moose and possible sib Bull, Moose Alley Logging Rd, along NH-Maine border, just under Canadian border, May 2022

Moose Cow, Moose Alley Logging Rd, Pittsburg, NH, along NH-Maine border, just under Canadian border, Sept 2022

Bull Moose, Moose Alley Logging Rd, Pittsburg, NH, along NH-Maine border, just under Canadian border, Oct 2022

Cow and calf, Lolo Pass, Montana-Idaho border, August 1990, by Steve or Dan Hall

What are we reading? Click on image to go to Amazon link

| Home |

Wolf |

Eastern Coyote |

Red Fox |

Arctic Fox |

Bobcat | Moose |

Opossum | Osprey | Bald Eagle |

|

Artists Home |

ADK Vacation Rentals |

ADK Real Estate |

|||||||||||

Photographs from Adirondack Habitat Awareness Day

Contact

Information

Adirondack Wildlife

Steve & Wendy

Hall

PO

Box 360, 977 Springfield Road, Wilmington, NY 12997

Toll Free:

855-Wolf-Man (855-965-3626)

Cell Phone:

914-715-7620

Office Phone 2:

518-946-2428

Fax: 518-536-9015

Email us: info@AdirondackWildlife.org