Why do we sometimes see lone Bear Cubs in Autumn?

Clockwise from upper left, Mama Grizz with 2 cubs in Yellowstone, May 2016, Mama grizz with cub in Teton, May 2018, young grizzly in Denali Nat'l Park in Alaska, May 2012,

and Yellowstone black bear with collar and ear tags, May 2018, all by Steve Hall, Luvey, one of 2 Wildlife Refuge ambassador cubs by Joe Kostoss,

| Barnabee, a Rehab Black Bear,

Nursing Her Cubs |

Come meet our ambassador black bears, Luvey and Ahote, at the Adirondack Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Hanna Cromie.

| The Unusual Life of Barnabee the

Bear |

Adirondack Black Bear by Deb MacKenzie, 2012, stopping a spinning watering source to get a drink.

|

"Exit,

pursued by a bear."

Shakespeare, Winter's Tale |

|

Black Bear: Ursus americanus Grizzly Bear: Ursus arctos horribilis Order: Carnivora Family: Ursidae Genus: Ursus Appreciating

Bears through the Seasons Published through

Adirondack Almanack at http://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2015/04/appreciating-bears-through-the-seasons.html#more-53143 Our

nightmare vision of the grizzly

prowling just outside the dissolving glow of the camp fire’s light, or

the fear

that we’ll lose our vegetable garden or livestock or trash barrels to a

marauding black bear, is balanced by the almost comical and brilliant

attempts

of the bear to figure out how to break into our stored food and trash,

or the

manner in which bears routinely entertain themselves and each other

with the

natural toys and circumstances nature provides, as when we see bears

sledding

on their butts. Curiosity and play are characteristics of higher

mammals,

particularly in predators like humans, wolves and bears, which often

lead to

opportunities to feed one’s self and one’s family. Where

did they come from, and when? The

ancestors of modern North

American bears evolved in Asia during the Pleistocene, wandering over

to Alaska

during several appearances of the Bering land bridge, between the

Bering and

Kamchatka Peninsulas. Advancing and receding glaciers, fueled by

evaporating

sea water, caused ocean levels to alternately drop and rise, exposing

and

submerging the Bering Strait. The common

ancestor of american black

bears and asiatic black bears came across half a million years ago, and

it is possible

that black bears adapted to climbing trees not only to exploit a wider

range of

food sources, but to escape the larger, faster and more strictly

carnivorous

short-faced bear, which, fortunately for us, joined the extinction

parade about

5,000 years ago. The glacially isolated polar bears split off from

grizzlies in

Asia about 130,000 years ago, and followed grizzlies across the land

bridge

about 100,000 years ago. Grizzlies stayed bottled up in Alaska for a

while, waiting

as the interglacial valleys between Alaska and the lower forty-eight

opened and

closed, and also possibly thanks to the presence of the same

short-faced bear

in the areas that became Canada and the U.S. These

factors set the pattern for survival for each species:

black bears tend to retreat, often up trees, while the heavier,

stockier

grizzly, evolving in the more open tundra and taiga, areas with fewer

and

smaller trees, developed the best-defense-is-a-great-offense approach

to

survival. How many

are there, and where are they found today? There are

about 500,000 black bears

in North America, probably 7,000 across their currently expanding range

in New

York State, with more than half of these within the Adirondack Region,

about a

third in the Catskills, and most of the balance expanding across

Central and

Western New York. Hunters took 1,628 black bears in New York State in

2014. Black bears

are the only bear found

uniquely in North America, and they tend to live where there is forest

and

vegetation for cover, and swamp, as in the east, or in the mountain

areas out

west. As with a slew of other mammals, bears have learned that while

human

beings mean hunting, in many areas, they also mean food and sustenance,

particularly when the bear’s natural sources of food fail, as when

drought

wiped out the Adirondack berry crop in the summer of 2012, driving so

many

bears into camp sites and back yards. There are

about 60,000 grizzly bears

in North America, sweeping across Alaska, the Yukon and the Northwest

Territories, spilling down the extensions of the Rocky Mountains,

through

Alberta, Saskatchewan and British Columbia, through Montana and Idaho

into

Yellowstone, with a diminishing presence on the surrounding prairies.

The

principal difference between inland grizzlies and the Alaskan coastal

brown

bears are the rich salmon diet of the latter. Why

you should never feed a bear Bears are

opportunistic, omnivorous

feeders, creatures of habit, who will continually revisit areas where

they have

found food in the past, whether those food sources are natural, or

provided by

human activities. With regard to the latter, this is why it is almost

always a

mistake to feed a bear: if you’re camping out in the High Peaks, and

you

purposely or inadvertently provide food for a foraging black bear, you

pretty

much guarantee that the next camper will have to deal with that bear’s

expectation that humans mean food. Similarly, because we experience

bears as

large and intelligent mammals, sometimes frightening and sometimes

entertaining,

we have a natural tendency to sympathize with their plights,

particularly in

the case of orphaned cubs and yearlings. Mature bears

are unique among the

larger North American mammals in that hunting is their number one cause

of death.

As with most other wildlife at any age, starvation is the main cause of

mortality among cubs and yearling bears. At the same time, bears, like

deer,

have discovered that suburban America is not only a great place to

forage for

food, but relatively safe from hunting, as local laws tend to forbid

firearm

discharge within 500 feet of a dwelling. Black

Bears Black Bear

boars range from 150 lbs.

to 550 lbs., with 300 lbs. being about average, while sows range from

90 to 300

lbs., with about 170 being the average. Black bears live to about 15

years in

the wild, and sometimes twice that in captivity, when their number one

challenge in life, food, is removed as an issue. Black bears walk

pigeon-toed,

but can run up to 30 mph. They’re characterized physically by shoulders

large and

powerful, though lacking the thick knot of muscles grizzlies have

between their

shoulders, and a straight facial profile which is often described as

“roman”,

as opposed to the grizzly’s more dish-shaped profile. In addition

the black bear’s dark

claws are shorter and more curved, adapted to climbing, while the

grizzly’s

claws are longer, less curved, lighter shaded and adapted for digging

out

rodents and plant tubers. A black bear’s paws are considerably more

dexterous

in manipulating objects than their appearance would suggest, and their

ears are

larger and more clearly defined than those of the grizzly. Black bears

mark

their presence by biting and clawing trees, rubbing their backs up and

down on

tree trunks, and by a peculiar stiff-kneed weight pressuring of their

front

paws into the ground, leaving nearly perfect prints. Bears have

the most sensitive

mammalian nose, more sensitive than even wolves. They have better

hearing than

people possess, and black bears apparently have sufficient color vision

acuity,

that, according to Jeff Fair, in “The Great American Bear”, they can

recognize

rangers in the Smokies by uniform and by car. Black bears, like

grizzlies, come

in various shades, from the predominant black of the eastern black

bear, and

occasional cinnamon in the Midwest, to sometimes brownish out west in

grizzly

country, a convenient evolutionary adaptation to resemble their more

imposing

grizzly cousin, to the blondish and whitish bears of British Columbia,

the

famous spirit, or ghost bear, the Kermode bear. Territory Bears are

not as strictly

territorial as wolves are, and their territories vary by gender,

availability

of food, time of year, and the presence of tolerant neighbors. Females

are more

territorial than are males, and sows’ territories are often bordered by

the

smaller territories of their dispersed daughters. Dispersal is what

takes place

when yearling cubs are booted out of their mother’s territory by an

eager-to-mate-again Mom, sometime in June after some of her cubs may

have spent

their second winter with her. Some Adirondack cubs disperse before that

second

winter. Bear “family life” is essentially about mom and cubs. Once a

young male

has been booted from Mom’s territory, or dispersed on his own during

their

second spring, his only future interaction with sows will be during

mating

season. Territory

defense has more to do

with protecting food sources against other bears than, say, the danger

to cubs

of wandering male bears (a danger more characteristic of grizzly

bears), so

allowing her daughters to stake out adjacent territories gives Mom an

effective

buffer zone against general food poaching by strangers. Average female

territories in New Hampshire and Maine are about ten square miles,

while males

may cover anywhere from 15 to 70 square miles. Male yearlings are more

apt to

wander around in search of their own territory, but territories are

commonly

violated by the presence of short-term seasonally available food in any

given

area. Through

the Seasons – Pre Hibernation Bear

activity is driven by the

seasons, particularly with respect to food availability, mating and

giving

birth. The bear’s specific form of hibernation is what really

distinguishes bears from other mammals, so we’ll start with the bear’s

activities during late summer and autumn. Since bears don’t eat while

hibernating, they go through a period of “hyperphagia”, or overeating,

in Fall,

gradually increasing their consumption until they spend about 20 hours

a day

eating, consuming, for example, American mountain ash berries, black

cherries,

mountain holly fruits and hazelnuts, gradually switching to wild apples

and

raisins, arrow wood, and finally that “hard mast”, beechnuts and acorns

in late

September and October. Out west the

hard mast consists of

white bark pine nuts. A larger than average hard mast harvest

will result

in fatter bears, which in turn will result in more cubs born to

pregnant sows

during hibernation. If the following year features droughts, this will

result

in thinner food yields, and too many cubs trying to feed themselves on

too few

berries, acorns, etc., as Nature adjusts the balance of supply and

demand. You

may have spotted a “bear’s nest” in a beech or oak tree, where a black

bear has

climbed out on a limb, reaching out and pulling in to him the nut laden

branches. Prior to hibernation, it is literally true that a fat bear is

a

healthy bear, and they’ll go from consuming 5 to 8 kilocalories a day,

to up to

20. A bear is

ready to hibernate when a

trigger-like physiological mechanism causes the bear to gradually stop

eating

and drinking, as their body begins to metabolize the fat they’ve been

building

up. They walk around in a kind of pre-hibernation daze, looking for a

location

to den up. For pregnant sows, this may begin in late September,

followed by

sows with first year cubs born the previous January, and finally barren

sows.

Boars may not begin hibernation till late October or November. Curiously,

it has been reported that

some boar grizzlies in Yellowstone may skip hibernation, as wolves are

apparently

such good providers of left-overs, the grizzlies can appropriate

abandoned or

inadequately guarded carcasses. Unlike your dog, wolves have to

navigate

between high food availability and no food availability, so when the

pack

succeeds in killing an elk or moose, the wolves will gorge themselves,

eating

up to 20% of their body weight in one sitting, becoming “meat drunk”.

Recall

last Thanksgiving dinner, how you fell asleep on the couch during the

second

quarter, and you’ll get the picture. Yellowstone grizzlies may be able

to

access enough protein to avoid hibernation altogether. This is a risky

approach, however, as successful denning is based on metabolizing fat,

not

protein, so the grizzly may find himself in trouble if midway through

winter,

his carrion food supply is seriously diminished. Denning

and Hibernation Dens may be

caves, hollows in trees,

an excavated hollow under a fallen tree’s root base, under the porch or

foundation of a seasonal cabin, and for some boars, just a clearing

with sufficient

wind break surrounding it, and a snowy blanket to augment the bear’s

winter

coat and keep the bear warm. Pregnant sows, and mothers who sometimes

have

yearling cubs with them, naturally seek those dens with more security.

Bears

may gather and line the dens with fallen leaves, pine boughs, and other

materials to make for a more comfortable and well insulated bed. Hibernation

may be defined as the

seasonal reduction of metabolism, concurrent with reduction in food

availability and temperature. In short, just as birds of prey migrate

not

because of the cold, but because the hibernation of many prey animals

deprives

them of a survival-enabling quantity of potential prey, so the main

reason

bears hibernate is as an efficient response to the hardships of feeding

oneself

during winter. Bears are

sometimes described as not

“true” hibernators. This is because while their heart rate may slow

down from

50 beats per minute to about ten during hibernation, their body

temperature

only drops about 12 degrees, whereas the body temperature of most

hibernating

mammals may drop to a few degrees above freezing. On the other hand,

while

bears may indeed rouse, and walk around during balmier winter days,

they can go

through their entire hibernation without having to urinate, defecate or

ingest

food, while the “true” hibernators have to do all these things from

time to

time, during hibernation. The reason

for this is that bears

spend their hibernation burning the fat they ingested during

hyperphagia,

shedding 25 to 40% of their body mass, but not lean body mass, such as

muscle

tissue, bone and protein. I can picture the late night TV ads already:

“SHED

WEIGHT WHILE HIBERNATING…. er… SLEEPING!” All kidding aside, medical

research

is very interested in understanding bear hibernation because of the

many

possible human medical applications, which include gallstone treatment,

kidney

disease, muscle cramping, bone calcium loss, renal disease,

anorexia,

skin regeneration and suspended animation. Imagine future astronauts

traveling

to distant planets while in a state of hibernation. Metabolizing

fat produces more

energy and water, but less urine, which ends up being recycled anyway.

Urea in

the blood is converted into CO2, water and ammonia. During a process

termed

“nitrogen shuttle”, ammonia and glycerol produce amino acids and

protein. Three

grams of urea nitrogen becomes 21 grams of protein, enough to develop

one cub.

The period of hibernation is a function of latitude and climate, such

that

while a Florida black bear may hibernate for only two months, one in

the Yukon

may do so for up to seven months. Winter

and the Birth of Cubs What all

this process means, in

effect, is that hibernating sows give birth during a period of virtual

starvation. Bears mate in late June or early July, and sows are

promiscuous by

nature, sometimes mating with a number of boars, such that cubs of the

same

litter may have different fathers. Sows experience delayed implantation

of

blastocysts, becoming pregnant only after they have successfully

prepared themselves

for hibernation through hyperphagia. The blastocysts of a

starving sow

will dissolve, thus preventing the added stress of giving birth to an

inadequately prepared sow. While

litters of two cubs are

typical, in areas of abundant food, sows may produce up to six cubs,

each

weighing about 12 ounces. Mama’s milk, delivered through six

nipples, is

25 to 30% fat, low in carbohydrates, and high in ash, calcium and

phosphorous.

Orphaned and abandoned cubs may be successfully placed with nursing

sows at this

age. The cubs grow quickly, even as Mom continues to shed body fat, and

will be

about ten pounds by April. Spring

Fever When Mom

leads her cubs out of the

den in spring, she continues in a state of biochemical narcosis, still

metabolizing fat, while losing weight, and nursing her cubs, who are

growing

rapidly. After a week or so, mom starts foraging, finding squirrel

caches left

over from winter, eating grasses, skunk cabbage and fiddleheads,

teaching her

cubs what to eat and where to find it. Catkins, roots, corms, early

fruits and

leaves, vegetation low in woody cellulose, round out the spring diet.

Carrion,

the bodies of animals killed by winter, as well as any deer fawns or

moose

calves the bears come across while foraging, bring much needed protein,

as do

ants, ant pupae, yellow jackets and bees, which appear on the menu in

June. Summer

Romance Summer

brings mating season and the

soft mast of berries. Sows which still have yearling cubs with them,

are

anxious to mate again, and begin rejecting their cubs. At this point,

the cubs

have spent more than a year learning the ropes from Mom, and are ready

to take

care of themselves, a condition Mom encourages by displays of

impatience,

charging her cubs when they try to follow her, and making it clear she

wants

her shadowing offspring to leave her alone. Siblings may eventually

wander off

together, and learn while foraging together that companionship is

great, except

when a shared limited food source means not having enough to eat, which

may

lead to the siblings striking out on their own, with females trying to

establish territories adjacent to Mom’s, while males look for

territories not

dominated by larger males. Males detect

females going into

estrus in late June and early July, and may begin tailing prospective

females,

waiting for signs of receptivity. The boars may forage and feed

alongside their

prospective sow, waiting for her to signal readiness, also fending off

approaches by other males, who may test their resolve with respect to a

particular sow. Much of this effort may be wasted, as sows are

promiscuous, and

may end up mating with more than one male anyway, with the interesting

result

that litters may have multiple fathers. Copulation may last up to 30

minutes. Meanwhile

the berry crops start

bearing fruit, pin cherries, sarsaparilla berries and blueberries in

July, and

red raspberries, choke cherries, blackberries and dogwood fruits in

August. In

good years there may be plenty of soft mast for everyone. Just as

Alaskan brown

bears flock to salmon streams, and tolerate the presence of other

bears, and

even human fisherman, thanks to the numbers of migrating and spawning

salmon,

so a rich crop of soft mast may find black bears eating these berries

exclusively for many days, often within sight of one another. Keeping

Bears away from Homes and Camp Sites How do you

keep bears out of your

camp site? In the case of camping in the High Peaks of the Adirondacks,

they’ve

made it academic: you must have with you an approved bear canister for

food

storage. More generally, never cook or store food anywhere near where

you plan

to lay out your sleeping bag. If you’re staying in a lean-to or tent

next to a

campfire, don’t cook over the campfire, as the odor of dripping fat and

grease

will be just as attractive to the bears, as actual food will be. For

the same

reason, heat food over your portable camp stoves far from the sleeping

area. Before the

canister law, folks in

the high peaks would typically store all food, as well as implements

for eating

and cooking in a bag, which would be hung from a branch high

enough, and

far away enough from the tree trunk, and far from the sleeping area.

Better to

watch the bears at a distance, figuring out how to reach your suspended

food

cache, than to have them in camp with you. If black bears are attracted

to your

campsite anyway, bang pots together, clap hands, yell at them, shine

lights at

them, in short, make their fear of your noisy dissuasion overcome their

attraction to the odors of food. How do you

keep bears out of your garbage and garden at

home? For the former, use approved bear-proof garbage containers, like

the ones

pictured. Only place your pet food bowls outside while your pets are

actually

eating, and only hang your bird and suet feeders during winter, when

the bears

are hibernating. You shouldn’t be feeding birds during the other three

seasons

anyway, as they have to learn to forage and store food, if they’re

going to

survive during periods when you’re not feeding them. Keep the compost

pile far

from the house, as it will absolutely attract bears, or locate it next

to the

vegetable garden, and use a solar electric fence to surround the

garden,

compost and any bee hives you keep on your property. Are

Bears dangerous to people? I once heard

George Carlin open a

set by saying that “you never hear about a bear until he bites

someone”, and

the audience laughed like that was the funniest thing they had ever

heard, when

in fact, it was an accurate description of how our media works. This

isn’t

about any particular political point of view. It’s simply a reminder

that all

forms of media face the challenge of attracting and retaining readers,

viewers,

whoever, and they often do so by taking the exceptional and wildly

improbable,

and presenting it as the state of expectations. Let’s face

it, we want to be

frightened. We want to say, “that could have been me”, or to

paraphrase

Carlin, nobody wants to read a story that tells us 50 million people

landed or

took off safely in jets from Kennedy airport last year (which is

accurate). They

just want to read about the jet that crashed, or in general, about

human

misfortune. Think “Bart the Bear”, and any of his movies, or “The

Grey”, that

ridiculous movie about clunky-looking wolves attacking plane crash

survivors,

in which even the story line makes zero sense, and is merely employed

to set up

the carnage that follows. There are

about one to three fatal attacks

by grizzly bears on people in North America in any given year, with the

average

over the last century being two. Most attacks are related to surprising

a

grizzly, either a sow protecting her cubs, or a bear protecting the

carcass of

an animal that it is consuming. While the very thought of an attack by

a bear

is quite terrifying, the logical question should be, how many people

see bears

up close in any given year? This is a

very large number. Using

just Yellowstone National Park, the only Park for which I could locate

stats,

in 2008 alone, over 1,000 people reported seeing grizzlies, which

likely means

that five times that many saw grizzlies and didn’t report the sighting

to any

authorities, like rangers, etc. Over the

last 25 years, I’ve seen

many grizzlies, some in National Parks like Denali or Banff, some at

private

camps like Knights Inlet on the B.C. coast, and many of them fairly up

close,

where one of the bear’s options was to whack me, including the one in

Denali three

Springs ago, whose photograph appears above. When it comes to

black

bears, millions of people see black bears each year, and yet, there is

a fatal

encounter about once every four years. In fact, your chances of being

killed by

lightening or a spider bite, or an attack by a dog, are very much

higher, even

in bear country. When it comes to bear encounters, think statistics,

not scary

anecdotes, which play into our deepest fears, and if you’re truly

interested in

bear attacks as a social phenomenon, read the Stephen Herrero book,

“Bear

Attacks, Their Causes and Avoidance”. The only

physical attacks by a black

bear in the Adirondacks that I am aware of, was the September 2013

incident on

the Placid Northville trail, when a female hiker was followed by three

bears,

until one got too close, and she stabbed it with her knife. I don’t

know

whether this courageous young woman was carrying food, or whether the

incident

was driven by the bears’ natural curiosity. There was an incident in

the

Catskills years ago, when an infant was snatched from a carriage left

outside

at a camping area known to be frequented by bears. When you measure

these

stories against how many of us have seen bears up close in the

Adirondacks,

it’s pretty clear that bears will flee most of the time, and decide to

pursue

physical contact almost never. I’ve never felt the need to carry pepper

spray

in black bear country. What’s

the safest protocol when meeting a bear? So… what

should you do when you see

a bear? Well, for starters, get your camera ready. Never run, as the

slowest

bear in history, is faster than Usain Bolt, the Olympic sprinter.

Contrary to

Hollywood movies, when a bear stands up to look at you, they’re first

trying to

figure out what you are, so they get nature’s

most sensitive nose higher in the air, doubling or tripling their

olfactory

range, in the hopes of identifying you. Grizzlies are obviously more to

be

concerned about than black bears, so if a grizzly stands and looks at

you, but

doesn’t get down and leave, this may mean he can’t figure out what you

are. If

you’re wearing a hat, gently waft it in the bear’s direction, so that

he can

smell that you are a human being. If a black bear feels threatened, it

may

initiate a series of bluff charges, which will almost certainly end in

the bear

veering off. Chomping or clacking the jaws is generally also a bluff,

but with

grizzlies, may very rarely be followed by a charge ending in contact. Many folks

carry firearms in bear

country, but in the rare case of a grizzly attack, some people have

been killed

by the bear they just shot. I prefer carrying pepper spray in grizzly

country,

because a face full of pepper spray, literally turns you into super

skunk in

the bear’s eyes. The key with pepper spray is to wear it on your belt,

and

obviously have it in your hand, ready to use, the second it becomes

clear that

the bear may choose contact. Wearing “bear bells” on your pack in

grizzly

country, may lessen the danger of surprising a grizzly at close

quarters, as

they will hear you coming, and likely flee the scene. Seeing a

bear in the wild is an

exhilarating experience you’ll remember for the rest of your life.

Never

approach a bear for that closer shot, as some grizzly attacks followed

the

bear’s perception that you didn’t just happen to be there, but were

actively

following them. If you unexpectedly find yourself near a bear, and the

bear

shows agitation, like swiping at the ground in front of them, emitting

a loud

“woof” sound, or engaging in bluff charges, never run, as this invites

pursuit. You are not

the bear’s natural prey,

and you want what the bear wants, peaceful and dignified disengagement,

so speak

clearly but gently to the bear, to let it know that you’re aware of

their

presence, and that you are not a threat. Never stare at the bear, as

this may

be taken as a confrontation, but also never turn your back. If you can

safely

back away, while still looking in the bear’s general direction, they

will likely

take that opportunity to flee. Suggested

reading for bear lovers: Benjamin Killam: Among

the Bears, and Going Out on a Limb; Jeff Fair: The Great American Bear;

Stephen

Herrero, Bear Attacks: Their Causes and Avoidance; Dave Taylor: Black

Bears: A

Natural History, all available through Amazon. Best web sites: Wildlife

Research Institute: http://www.bearstudy.org/website/;

North American Bear Center: http://www.bear.org/website/ |

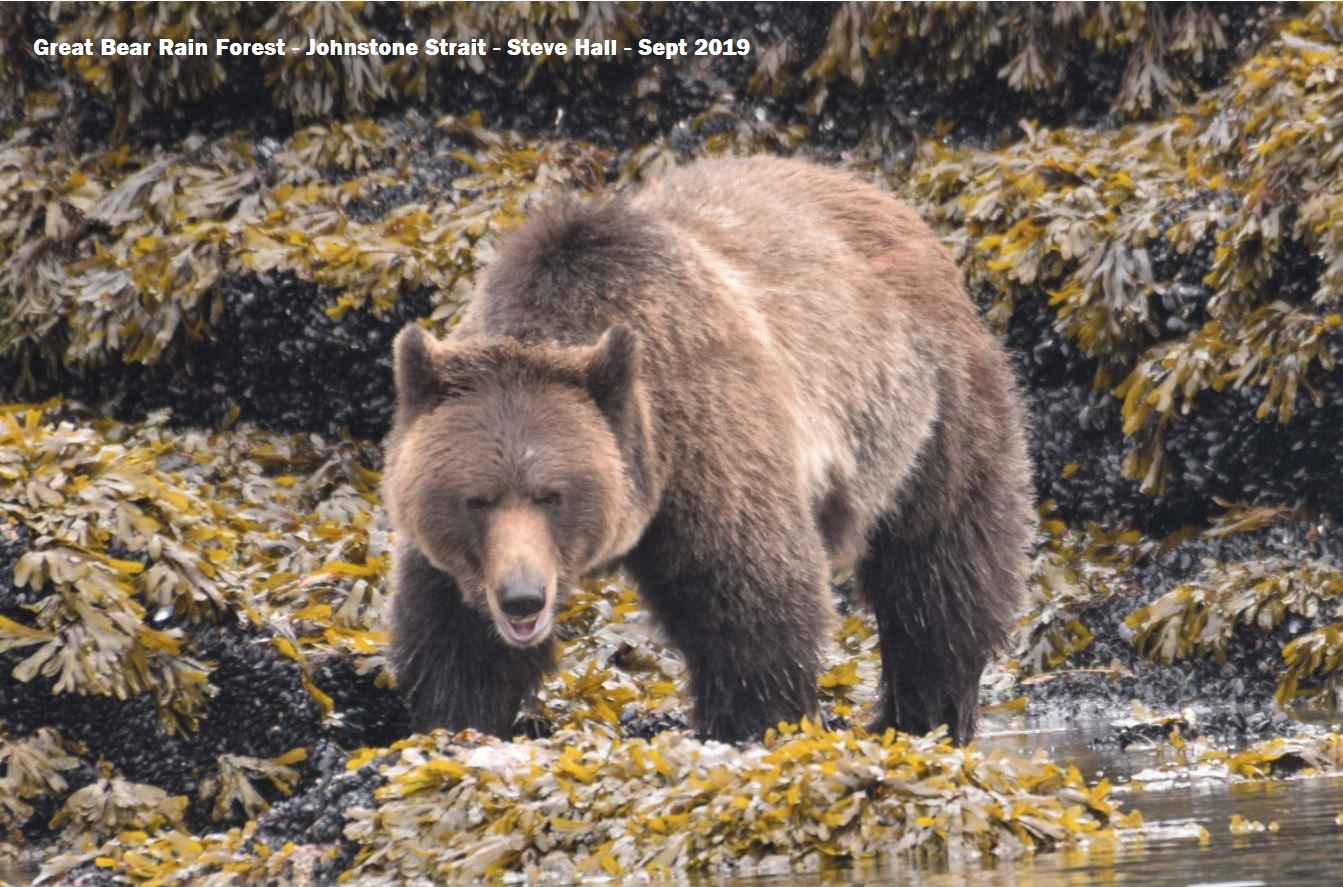

Above and below, Grizzlies in Great Bear Rain Forest, Johnstone Strait, Sept 2019, by Steve Hall.

If the salmon run fails, mussels and barnacles are the main diet at low tide.

Left, expanding black bear range in N.Y., from the DEC, and physical comparison of black bear vs. grizzly.

Adirondack Black Bear by Darrell Austin, left and Alaskan Brown, in Kenai, Alaska, May 2012, by Steve Hall

Denali Grizzly, by Alex Hall, May 2011

Yellowstone black bear by Alex Hall, May 2013

Yellowstone grizzly bears by Steve Hall, May 2016: sow with 2 cubs.

L to R: Black bear sow with yearling cinnamon cubs, May 2016, Yellowstone, & treed Black Bear cub, by Steve Hall

Short-faced bear, a Pleistocene predator, fortunately for us, now extinct.

left to right, black bear, grizzly and polar bear ranges, from Defenders of Wildlife.

left, DEC biologists radio-collaring "yellow-yellow", world champion bear cannister cracker, and an unwanted picnic guest.

The Great Bear Escape, March 2019.

The bears went exploring for 2 weeks, and then Luvey, the brown phase black bear, followed Hanna and Steve home, 4 miles through the woods. 2 days later, Ahote, the black phase black bear, followed Hanna and Caroline 1 mile home to the Wildlife Refuge.

Examples of bear-proof trash barrels being tested. by grizzlies.

Adirondack Wildlife is available to do educational presentations at public venues.

What are we reading? In particular, we found "Great American Bear" very useful for a layman's understanding of hibernation, etc.

Click on image to go to Amazon link

Visit the North American Bear Center in Ely, Minn., great education center

Come meet our Ambassador Bears & Learn all about Bears

| Home |

Release of

Rehabbed Animals |

Learn

About Adirondack & Ambassador Wildlife |

Critter

Cams & Favorite Videos |

History

of Cree & the Adirondack Wildlife Refuge |

|

Artists Home |

ADK Vacation Rentals |

ADK Real Estate |

|||||||||||

Photographs from Adirondack Habitat Awareness Day

Contact

Information

Adirondack Wildlife Refuge & Rehabilitation Center

Steve & Wendy Hall

PO Box 555, 977 Springfield Road, Wilmington, NY 12997

Toll Free: 855-Wolf-Man (855-965-3626)

Cell Phones: 914-715-7620 or 914-772-5983

Office Phone: 518-946-1197 or 518-946-2428

Fax: 518-536-9015

Email us: info@AdirondackWildlife.org